Gallery 232, second floor

Main Building

Magnificent temples are not the only place where Tibetan altars are used. Tibetan-Buddhist lay practitioners usually reserve a sacred space in their homes where ritual worship is performed daily. Wealthy families often designate one or more rooms in their homes as altar-rooms where they install fabulously painted wooden altars that house sublime sculptures, sacred books, and ornate ritual implements. In 2004, the Museum acquired a spectacular Tibetan altar adorned with intricately carved niches and lively paintings that highlight domestic themes. However, many layers of smoke and oils obscured the brilliant colors of the altar's paintings—a result of countless burnt offerings of incense and butter-lamps. This installation displays—for the first time—the Museum's newly cleaned altar and discusses both the conservation of the altar as well as its cultural context. X-rays and samples of paint-layers reveal hidden mysteries of the altar's construction and decoration, while elaborate ritual objects, such as incense burners, libation ewers and butter-lamps, illuminate the ritual beauty of Tibetan devotional art.

A domestic altar in ritual use.

Most Tibetan-Buddhist households have a portion of the house set aside for religious activity. In wealthier homes, one or more rooms may be dedicated as altar-rooms. Traditionally, devout families worship daily at this altar, offering incense, beverages, and foods to the deities they house. For special occasions (such as weddings, religious holidays, or specific ceremonies to bring luck to the family or to cure family members' illnesses), religious practitioners are invited to a family's altar room to read prayers and perform rituals. In the past most Tibetan families had relatives who became monks or nuns, thus religious practitioners called for these services were often related to their patrons.

Statues, ritual implements, prints, and books are usually placed in the central niches of Tibetan-Buddhist altars. Each item is imbued with specific meanings. For example, necessary components of a consecrated altar include symbols of the Three Gems and Five Senses.

Significance of the Three GemsObjectSymbolism Body Teacher Buddha Speech Teachings Dharma

(Buddist Teachings) Mind Students Sangha

(Buddist Community) Symbols of the five senses are often found in Tibetan-Buddhist paintings of deities. How these senses are represented within the painting depends on the character of the deities depicted in the painting. The five senses are usually represented on an altar by the following objects, which are inserted into the niches of the altar: butter lamps (sight), incense holders and flowers (smell), cymbal and bell (sound), ceramic lemon fruit (taste), khatak offering scarf (touch).

Peaceful and Wrathful Symbols of the Five Senses Peaceful Symbol Sense Wrathful Symbol

Mirror Sight

Eyeballs

Incense Smell

Nose

Cymbals Sound

Ears

Peaches Taste

Tongue

Cloth Touch

Cloth Usually several images (both paintings and sculptures) of a variety of deities are included with Tibetan altars. What specific deities are chosen for an altar depends on sectarian affiliations and personal preferences of the devotees who will use the altar. For example, followers of the Nyingma religious order of Tibetan Buddhism most often have statues of the famous exorcist Padmasambhava, while followers of the Gelugpa religious order frequently include a statue of Tsongkhapa, the founder of the order. One of the most popular deities regardless of sectarian affiliation is Tara, Goddess of Compassion, who is worshipped as a benevolent intercessor.

Offerings are placed on or next to Tibetan altars. Water, milk, alcohol, grains, incense, and butter lamps are essential to worshiping the deities believed to live within consecrated images.

Ritual offerings of water, grains, incense, lamps, and torma dough cakes.

Daily rituals include changing the water offerings as well as lighting fresh incense and new butter lamps. Offering scarves, called khatak in Tibetan, may be hung on an altar or wrapped around some of the altar's statues or books. Often, these scarves are blessed by a Lama. The blessed scarves are then placed on an altar to transfer the power of the Lama's blessing to the altar. These types of ritual offerings create physical residue (such as coatings, soot, and fibers) that leaves clues as to how the Museum's altar was originally assembled and used.

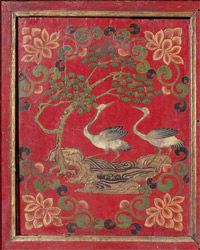

Altars, like the Museum's, usually display a range of symbolic offerings in the form of wood-block prints, ritual dough cakes, or the items themselves. For example, on the interior of the panel decorated with cranes are two fragments of a print depicting Amitabha (Bodhisattva of Infinite Light) and a parasol. The parasol is one of eight auspicious symbols that frequently decorate altars. Prints like this one are used to bring luck to the worshipers.

Tibetan-Buddhist ritual use of many religious artworks often necessitates that these artworks be consecrated. Ritual specialists are required to consecrate an object for worship. The methods of consecration vary depending on the object consecrated.

For example, statues and stupas may be filled with empowered objects, such as paper prayers, incense, and votive plaques.

Paintings (lacking a hollow cavity) may be consecrated with inscriptions. The most frequent inscription found on Tibetan paintings are the sacred syllables om ah hum that symbolize the body, speech, and mind of the deity. These syllables are marked at the heart, throat, and head of a figure. Some figural representations are consecrated through an "eye-opening" ceremony in which the eyes of the statue or painting are colored last as part of ritual consecration. The act of consecration not only blesses the object, but is also intended to make the blessed work a nexus of spiritual power. Devotional adornment, perfuming, lustration, and touching the object further enhances its spiritual potency. Without consecration, the artworks are only reminders of Buddhist elements, rather than empowered active objects. The physical remnants of certain types of oils and soot (from incense, various liquids, and light offerings) signify the Museum's altar was once consecrated, at least through use.

The choice of colors and subject matter that adorns the Museum's altar demonstrates worldly themes, such as auspicious wishes for longevity, financial prosperity, and domestic happiness, as well as invokes local Tibetan protector deities.

Red is an auspicious color in Tibet and often denotes a religious context. Red is the color of temple wall exteriors and the color specified for clothing of Tibetan-Buddhist monks and nuns. Red borders always frame Tibetan paintings and often decorate parts of sculptures. In general, Tibetan-Buddhist art thrives on a rich variety of contrasting colors. For example, the vases that decorate the altar niches alternate between blue and green, while the center petals of the flowers on the lower panels of the Museum's altar alternate between red and orange. Paint colors made from precious and semi-precious stones and metals usually retain their color without fading over time while paints colored with vegetable dyes fade as they are exposed to light.

The lotus is one of the most important motifs in all Buddhist art. Rising from the mud above a pool of water and unfolding suspended in the air, the lotus is a symbol of purity and often indicates sanctified space or a sacred individual. A lotus decorates each of the protruding and receding notches on the altar's lintel. A single row of multi-colored lotus petals frames each of the three components on the top of the altar and a single row of red-and-gold lotus petals subtly separates the upper and lower sections of the altar. An intricate notched and painted border frames the center of the altar in a design named after a lotus, chutchi pem. The entire lower portion of the altar also is decorated with stylized lotuses and curling tendrils. Even the partitions between the niches are each decorated with a lotus that emerges from a vase. Alternating between blue and green, these vases represent endless wealth. Raised work called khungbur in Tibetan also decorates many of the panels on the upper part of the altar. Like the treasure-vase motif, the golden raised work and golden borders signify the wealth of the altar's owners, and is believed to attract additional wealth.

Tibetan iconography adopts some Chinese symbolism—but often in a way that is distinctly Tibetan.

Symbols of Health, Wealth, and Domestic Felicity on the Four Doors on a Side Cabinet

Two cranes (1), Chinese symbols of longevity and immortality, wade in the water in a wooded glade filled with a highly stylized pine tree. Cranes migrate north-south passing through Tibet seasonally, heralding the changing of seasons, and marking celebratory events in the liturgical calendar. Standing in a rocky landscape, this balding white-haired, long-bearded man (2) holds a staff that dangles a scroll and gourd as well as a red speckled fruit. Probably originating from one of the eight Daoist immortals of China (his Chinese name, fu, is a homonym for both "old man" and "wealth") Tibetans recognize this bearded old man as a symbol of longevity.

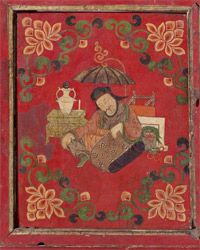

The man seated under a parasol (3) unfurling a roll of textiles in his lap most likely represents a successful merchant or trader. A golden or white vase (possibly representing porcelain) rests on a low table and a white scroll is partially unrolled next to a frame that suggests a kind of container used in trade. These goods (porcelain, paper, and textiles) may refer to the source of the original altar owner's wealth. Like the mated pair of cranes, these two deer (4)—a stag and a doe—are not only symbols of domestic harmony between man and wife, but also the Chinese name for deer (lu) is a homonym for prosperity and good health. Panels 1, 2, and 4 depict what Tibetans refer to as the Six Symbols of Long Life, namely an old man, rock, deer, cranes, water, and a highly stylized pine tree.

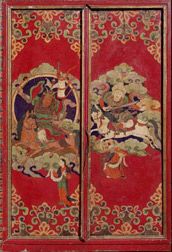

Protector Deities on the Two Doors of a Side Cabinet

On the left side panel (5), an equestrian warrior holds up a white, red-trimmed, spear-topped banner and brandishes a riding crop. He is possibly the epic hero Ling Gesar or a protector deity such as a Dra-lha or Srung-ma class spirit. Such classes of martial spirits most likely pre-date Buddhism in Tibet, but were absorbed into the Tibetan-Buddhist pantheon as protectors. Another protector of this type appears on the right panel (6) astride a white horse. He wears a turban and a different style of armor, wields a sword, and makes a threatening hand gesture. Similar to warrior costume still used in contemporary Chinese opera, both warriors have distinctive banners protruding from their heads—a device that was intended to make them more ferocious on the battlefield. The multi-colored tri-lobed clouds surrounding both warriors (5 & 6) are derived from Chinese artistic motifs and are called ruyi in Chinese after an auspicious fungus. They represent wish-granting clouds and indicate the celestial nature of these deities. A standing woman and a seated man (5 & 6) each raises up a white offering scarf (called a khatak in Tibetan) to these fierce warriors. The scarf-offering demonstrates fealty from the lay household to these deities.

Gallery 232, second floor

Main Building

Funds to conserve the altar generously provided by the Women's Committee of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Katherine Anne Paul • Associate Curator of Indian and Himalayan Art

Anne Kingery • Kress Fellow in Objects Conservation

Beth Price • Senior Scientist for Conservation